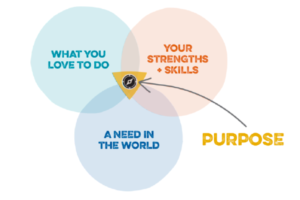

Purpose Compass

Students generate purposeful project ideas by personally identifying (1) a need in the world that moves them, (2) their skills and abilities, and (3) something they find joy and value in.

Students generate purposeful project ideas by personally identifying (1) a need in the world that moves them, (2) their skills and abilities, and (3) something they find joy and value in.

Students will:

In this lesson, students will practice brainstorming with a generative, nonjudgmental, “yes, and” approach, rather than a hypercritical “no, but” mindset. To help them warm up to creative and nonjudgmental thinking, play the following game.

Project Wayfinder partners with educators to design innovative learning experiences that foster meaningful relationships and guide students to navigate their lives with purpose.

How did students respond to this practice? Did they struggle with any of the circles? Did the process encourage them to put their ideas into action? How might they relate their ideas to what they’re learning in school?

Studies find that pursuing one’s purpose is associated with psychological well-being. For example, compared to others, people with purpose report they are happier, more satisfied with their lives, and more hopeful about the future.

For teens, purpose is related to indicators of academic success, such as grit, resilience, and a belief that one’s work is feasible and manageable.

In spite of the benefits, only about 20% of adolescents lead lives of purpose. Granted, the developmental task of teenagers is to discover who they are (identity) and what they want to accomplish that benefits the world (purpose); however, students who have a sense of purpose or are actively looking for one are propelled by a personally meaningful and highly motivating aim—they know what they hope to achieve and how academics can help. Hence, they are more likely to work hard and excel in school.

Do you want to dive deeper into the science behind our GGIE practices? Enroll in one of our online courses for educators!

Comments